It seemed fitting that on the 999th anniversary of Hanoi’s liberation from invading armies, I paid a visit to an old soldier. Viet Hong Lam Pham traded his gun for a paintbrush almost 40 years ago after being deafened during an American bombing raid during the Vietnam War, and is now an accomplished artist. I read his story in a Vietnamese newspaper and was impressed by his current efforts to mentor young artists. I decided to contact him, and after a brief email exchange, he invited me for a visit to his home/studio.

My interpreter and I arrived in his neighborhood, a maze of winding streets on the edge of Hanoi so narrow that only foot and motorbike traffic can get through here. We walked along, stopping frequently to ask directions. Everyone seemed to know just where he lived – old men, young women, boys, and girls all broke into smiles and instantly pointed the way as if we were following the yellow brick road to the wonderful wizard of Oz.

We finally stopped in front of a large gate and rang the bell. A young girl greeted us and we were escorted through a peaceful garden of plants, trees,  and small waterways to a large 3-story home of dark wood and stone. Mr. Pham met us at the door and welcomed us inside with a sweep of his hand – a bit formal of a gesture but I took an instant liking to this man with a kind countenance. We followed him into an airy and bright dining room with open doors that looked out onto the garden and courtyard. The inviting ambiance and calming effects of the feng shui design made me feel instantly at home.

and small waterways to a large 3-story home of dark wood and stone. Mr. Pham met us at the door and welcomed us inside with a sweep of his hand – a bit formal of a gesture but I took an instant liking to this man with a kind countenance. We followed him into an airy and bright dining room with open doors that looked out onto the garden and courtyard. The inviting ambiance and calming effects of the feng shui design made me feel instantly at home.

Mr. Pham poured us some tea and settled in to answer my questions. He joined the communist army when he turned 18, engaged in the wars of his country during the 1960s and early 1970s, and suffered two serious injuries before the blast that deafened him took him of commission for good at 28. Devastated by the loss of his hearing, he struggled to find the will to live, attempting suicide three times, until his artist father encouraged him to pursue this therapeutic vocation. Mr Pham went to art school where he met his future wife. “It worked out, you see. I met my partner. It was then that I started to realize that for everything bad in life, there is good to be found,” he explained. “You wait and you will see what it is.”

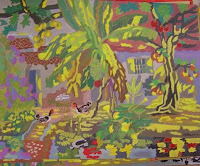

If 10 years of fighting wars during his formative years once hardened him, there was no indication of any of that now. In a process of healing, Mr. Pham tried to focus on the good things in life until the practice became as second nature as his adopted Buddhist faith. His paintings reflect memory snapshots of his military travels throughout Vietnam, but he only uses cheerful colors to convey them. “My father painted with dark colors but I only use the bright ones,” he said. “There is so much light in life. It makes my heart happy to focus on the good instead of the bad things.”

I learned that he can hear a little bit in one ear through the use of a hearing aid, but relies on lip-reading to understand what is being said. “I cannot hear well anymore since the bomb, but when I remove my hearing aid, I can concentrate better on my art. So you see? Again, there is good with the bad.” I nodded and explained that I frequently take my hearing aids off when I write – the abso lute silence can be conductive to creative work. He smiled at me, “Yes, see you understand. We share that. You and I.”

lute silence can be conductive to creative work. He smiled at me, “Yes, see you understand. We share that. You and I.”

Mr Pham invited me to his studio to view samples of his work. “I used to live in the Old Quarter, but then had to move to a bigger house.” He gestured at the paintings around him and laughed, ” Not enough room for all my art and my father’s art!” The work was truly creative – bright colors of water color and gauche paint splashed across rice papers in abstract designs and portraits of landscapes and people.

He mentors young artists now, including blind children. He explained that he teaches them the concept of hot and cold palettes by running cold water over their hands or hovering their hands over a flame, depending on the color being introduced. “The pictures of the blind children are the very best because they paint from the imagination. I do not have to teach them how to paint with feeling.”

He complemented the Global Foundation for the work we are doing. “it is important for both you and for others, to help the less fortunate turn bad situations into better ones.” He offered to introduce me via email to his circle of artist friends who may be able to lend suport. A kind and unanticipated gesture of friendship.

Our conversation complete, Mr. Pham escorted us out into the serene garden. He extended his hand to take mine and then leaned in to touch each of my cheeks to his own. His eyes crinkled into a warm smile and he paused before nodding his goodbye. No words needed to be said.

Thousands of miles away, there hangs a plaque above the players’ entrance to Center Court at Wimbledon that reads “if you can meet with triumph and disaster and treat those two imposters just the same, yours is the world and all that is in it.”